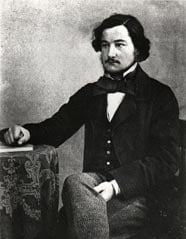

William Morris

William Morris aged 23

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834 at Elm House, Walthamstow. His father died in 1847 and soon afterwards the family moved to Water House, Walthamstow, now the home of the William Morris Gallery. Morris was sent to school at Marlborough in 1848 and afterwards went to Exeter College, Oxford, to study Theology, where he met Edward Burne-Jones who became his lifelong friend.

The stained glass workshop

It was on a trip to France where Morris and Burne-Jones decided not to take the Holy Orders but to dedicate their lives to art. Morris left college in 1856 and went to work for an architect G.E Street where he met Philip Webb. Burne-Jones moved to London and studied painting under the guidance of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Morris soon abandoned architecture and began to study painting under Rossetti’s guidance. He found his talents were more suited to decorative arts than painting and experimented with stained glass, ceramics, furniture, book design, wall papers and textiles.

The Firm

The dye house (ground floor) and the stained glass workshop (first floor)

In 1859 Morris married Jane Burden and a year later they moved into Red House, Bexleyheath, Kent, a house designed for Morris by architect Philip Webb. Morris and a group of friends (Rossetti, Webb, etc.) started to design and produce their own furnishings for the house. This led to the formation in 1861 of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

The ‘firm’ as it became known, set up in rented premises in Red Lion Square and soon prospered. Most of the early work was commissions from Gothic Revival architects for supplying them with stained glass and furnishings for church buildings.

In 1865 Morris and the firm moved to 26 Queen Square, Bloomsbury. The ground floor was converted into workshops and offices whilst Morris and family lived on the first floor. It was in the scullery where Morris and Thomas Wardle first started experimenting in the revival of vegetable dyeing, starting with embroidery silks.

In 1871 Morris and Rossetti took out a joint tenancy of Kelmscott Manor by the banks of the Thames in Oxfordshire.

Morris & Co

By the middle of the 1870s the Firm had started to run into difficulties. Morris wanted to expand but the other members found it more lucrative developing solo careers. Also Morris thought the other members profited from his labours so in 1875 Morris decided to dissolve the Firm set up under his own control as Morris & Co.

The new company soon expanded and opened up a shop at 449, Oxford Street. Morris was now turning his attention to woven fabrics and employed a French weaver named Louis Bazin who set up a Jacquard Loom in a new hired workshop at Great Ormond Yard, near Queen Square. After initial problems were overcome the first pattern, the Willow was produced at the end of 1877.

In the autumn of 1878 Morris and family moved to Upper Mall, Hammersmith, now the headquarters of the William Morris Society. Morris renamed the house Kelmscott House which was to become his home until he died. He set up several carpet frames in the coach-house and stables and started to produce handmade carpets which became known as ‘Hammersmith’ carpets.

By 1881 the Queen Square and Great Ormond Yard workshops were becoming cramped and were not able to accommodate the new looms Morris required. He decided to look for premises large enough to manufacture all his goods under one roof. He needed a works near a river suitable for vegetable dying, workshops for cloth printing, textile and carpet weaving, tapestry making and a stained glass workshop. At the time William De Morgan was also looking for premises to manufacture tiles which were sold at Morris’s Oxford Street shop. After rejecting premises in the Cotswolds and at Crayford, Kent, Morris visited the printing works at Merton Abbey and found it exactly suited his needs. William De Morgan also found premises at Merton Abbey and set up close by.

William Morris and the Merton Abbey Works

Morris purchased the site in June 1881. He refused to pull down any of the existing buildings and apart from some minor alterations they remained unchanged until the works closed in 1940.

The site Morris acquired was established in 1752 as a calico printing works and continued to produce calicos until the 19th century. The owners of the works before Morris acquired the lease were the Welch family who produced table-cloth.

Morris adapted the buildings to suit his needs. Next to the entrance to the works was the office and caretaker’s house, next door was the drawing and design room, next door again was the dormitory for the apprentice boys. The two-storey shed to the rear of the High Street buildings contained the dye vats on the ground floor with the stained glass studio on the first floor. Outside this building was a small single-storey weaving shed. On the south bank of the River Wandle was a large shed overlooking the millpond. The ground floor housed the carpet and tapestry looms with the first floor used for fabric printing.

Before Morris could start production a number of alterations had to be undertaken to the buildings. The sheds were strengthened, trenched and puddled to keep out the damp, roofs heightened and re-tiled to fit the looms, floors re-laid and eight (6- foot cubes) dyeing vats were sunk into the original floor of one of the buildings.

Furniture, tiles, embroidery and wallpaper were made elsewhere and not at the Merton Abbey works.

The Processes

Dyeing

Fabric dyeing was undertaken in the dye house in large sunken vats; smaller vats were used to dye the silk and wool yarns.

All the dyes Morris used were made from natural substances based on early herbal recipes. These dyes gave a softer tone to the textiles unlike the aniline dyes which gave harsh colours and soon faded.

One of the main reasons Morris decided to move to Merton was that he found the water of the Wandle ideal for dyeing. Many of the fabrics Morris & Co produced used the indigo discharge method. First the cotton cloth is dyed to a shade of blue in one of the large indigo dye vats and then the cloth is printed with a bleaching agent to remove the blue as the patterns requires. Mordants (fixing agents) are then printed on the white parts and the cloth dyed a second time with madder and again with yellow. The three superimposed colours gives green, purple or orange. The access dye was washed away and the colours set by passing the fabrics through soap at nearly boiling point. Afterwards the fabric was laid out in the meadow to dry.

Block printing

Block-printing was undertaken on long padded tables which ran the length of the workshop. The printer would first place the printing block on the dye pad and then press the block onto the cloth. The block was pressed down with the aid of a lead weighted mallet to produce an impression. The dye pads were carried on trolleys which the printer could pull along as he worked along the length of the cloth.

After the first set of impressions was dry a second set of blocks was printed on the cloth and the process repeated. Small pins projected from the blocks so each successive impression could be aligned. The early printing blocks were carved from pearwood which were later replaced by blocks with metal inserts padded with felt to hold the dye.

Stained glass

Morris based his stained glass on the style of the later medieval period which had an emphasis on rich glowing colours in a free-flowing pattern unlike the stained glass of the 17th and 18th centuries which were literally over-precise painted reproductions of medieval stained glass.

The designs for stained glass were first drawn on small sheets which were photographically enlarged to full size as a working drawing known as a ‘cartoon’. Different coloured glass was placed over the cartoon and cut to size. The stained glass artist would then place the individual pieces on his easel and paint on the design. These would next be fired in a kiln located next to the office. After firing the painted glass was leaded together to form the overall picture. The finished design was polished with linseed oil and bran polish to give a high gloss.

Edward Burne-Jones designed most of the stained glass made by Morris & Co but after Morris’s death Dearle became responsible for the artistic direction of the company’s stained glass.

Weaving

The looms Morris & Co used at Merton were the Jacquard looms invented in 1802 by a Frenchman, Joseph Marie Jacquard and became widely used from the 1820s. The advantage of using this type of loom rather than the more traditional draw-looms was that the Jacquard loom used a series of punched cards to lift the warp threads automatically, enabling a more accurate design. The cards could also be stored which meant that patterns could be easily and accurately repeated. The draw-looms were slower and the finished designs less accurate.

Morris spent much of his time in historical research at the Victoria and Albert Museum (then the South Kensington Museum) and was much influenced by the 14th century Italian textiles as well as Middle and Far Eastern patterns. Much of Morris’s designs were based on these early examples.

Carpet weaving

The carpets made at Merton Abbey were hand-knotted or tufted and continued to be known as ‘Hammersmith Rugs’ from their place of origin. This was to distinguish them from the machine-made carpets made by outside contractors.

Morris designed almost all of the firm’s carpets. He would produce a scale drawing, about one eighth of the full size. The design would then be transferred on to point paper, a squared paper with each square representing a single knot of the carpet. The point paper was hung on the loom and the design copied by the weavers. The loom consisted of two rotating horizontal rollers between which hung the vertical warp threads. Two-inch-long weft threads were knotted around the warp threads. As each row was finished the weft was beaten down and the process repeated. As the carpet progressed the upper roller unwound enabling a new section to be woven.

Mostly girls were employed in carpet weaving as their smaller hands were better suited to the intricate work. Each weaver would produce around two inches of carpet a day.

Tapestry

The tapestries were woven on high-warp looms. The high-warp or upright loom is a type of loom used in the late medieval period by Flemish tapestry weavers.

Almost all of the tapestry figures were designed by Burne-Jones. He would draw the figures around 15 inches high. The drawings were photographically enlarged full size, mounted, and Morris and Henry Dearle would draw in the foreground and background. The finished drawing was then placed against the loom and traced onto the warp. The tapestries were woven using the plain weaving technique which had a parallel set of warp threads interwoven across the warp with the weft threads. The weft treads were then packed down with a comb to hide the warp threads. Three looms were initially set up with three people working at each loom. Each weaver would sit facing the back of the tapestry with a mirror positioned in front to reflect the design.

Wallpaper

Wallpaper was not made at the Merton Abbey factory but by an outside contractor Jeffrey & Co. The process of printing wallpaper was similar to that of printing textiles. The paper was printed with wooden printing blocks, pressed down with the aid of a foot operated weight and the process repeated.

After William Morris died in 1896 the Merton factory continued production under his junior partners Frank and Robert Smith, with John Henry Dearle promoted to Art Director. Burne-Jones died two years later and the majority of the designs for wallpaper, stained glass, textiles and carpets fell to Dearle.

In 1905 Henry Marillier joined the company as managing director and the new company was named Morris & Co. Decorators Ltd. In 1925 the company was renamed as Morris & Co Art Workers Ltd. With the death of Dearle in 1932 the company lost its artistic strength, the quality of work gradually fell and with the depleting market the order books shrank. The company continued to decline until it went into liquidation in May 1940.